Mushrooms. Mushrooms everywhere.

Over the past few years, I’ve grown an interest in mushrooms. Going mushroom foraging. Determining what species a mushroom is, and what its family is. Is it food? Is it poison? Or something in between?

It all started with my partner running excitedly down from our previous apartment. It was fall, and she spotted something in the grass outside the window. It turned out to be shaggy manes. Towering, white mushrooms that look like handless hattifatteners. She came in with a pot full of them and made a delicious creamy soup out of them. I’d characterize their flavor as a mix of classic “mushroom” and asparagus, which is fits really nice during fall.

My partner comes from a family of mushroom identification experts, where both her parents were certified. There’s a difference between Norway and Germany, though. As an example, where Norway has plenty of destroying angels (Amanita virosa) , they barely exist in Germany, and where Germany has penty of death caps (Amanita phalloides), they are much more rare in Norway.

This began my journey of getting into mushroom identification. I’ve gone the typical route of jumping around to find anything edible into looking for the more obscure and poisonous. It’s like a treasure hunt. You never know what you may find! I think there must be a huge overlap towards people picking mushrooms and people owning metal detectors.

Since the shaggy mane day in 2020, we’ve acquired a shelf full of mushroom books, and we’ve found and identified hundreds of different species and families. I never thought I’d be able to identify mushrooms exclusively through smell, or to put raw mushrooms in my mouth for tasting whether or not it’s a good one—which is something you can do for russulas.

Last year I started joining an online mushroom class to help certify myself for mushroom identification. I didn’t take the exam then, but I wanted to push myself to take it this year, and as soon as it was possible to sign up for an exam, I did so.

Since this spring, I spent whatever opportunity I could find to look for mushrooms around. But unfortunately we didn’t have a particularly good spring or summer season. We found a few spring agorcybes (Agrocybe praecox) and I found a St. George's mushroom (Calocybe gambosa), and that was about it for quite a while.

Summer kept the dryness up, which didn’t bode too well for the mushroom season. I went up north to my parents, found a few mushrooms around. It was early, but I managed to find and identify sheathed woodtuft (Kuehneromyces mutabilis) as one of a handful of mushrooms. During July, russulas started popping up and we started getting a tiny bit more diversity, but they were small, few, and far between. I spent this month on categorizing, learning, and figuring out mushrooms.

In August, the hunt truly began. The list of mushrooms to know by species is around 150, and there are also a handful of families that one must know. At this point, I had seen around 30 or so mushrooms this year and around 70 or so of the list in total. Some are easy to identify even though you’ve never seen them in person, whereas others require you to recognize the smell, the color, the trees they grow under, and so forth.

We went to Germany, where the mushroom season had progressed much further, and I was able to tick off a lot of mushrooms I’d not seen before, including the the aforementioned lurid boletes (Suillellus luridus) and the giant puffball (Langermannia gigantea). The latter is a splendid food mushroom which adds a great consistency to the mix. It’s a bit like tofu in the sense that it soaks flavors.

Back home in Norway, the season started for real in the second half of August. I tried to attend every single coordinated mushroom foraging tours and guides that popped up in the local area. Through my local mushroom association, I was able to join a studying group with several other very talented and aspiring mushroom identification candidates. We gathered, examined, and discussed mushrooms at different locations. This way allowed us to learn from our common mistakes.

Every day after work, or on the way from or to work, I tried to go detours via small forests, close to trees, and see if there were any mushrooms popping up. One of the key elements to getting to know mushrooms is to be exposed to them. Touch them. Smell them. See them up close. Feel their texture.

In the weeks leading up to the exam, I worked hard on memorizing the norm list, which governs what mushrooms are edible, inedible, which are poisonous, and what a potential mushroom poisoning timeline would look like. For this, I used a phenomenal tool developed by a mushroom identification expert named Soppquiz. This allows practicing the different mushrooms’ statuses and attempting identification based on pictures. Highly recommended tool!

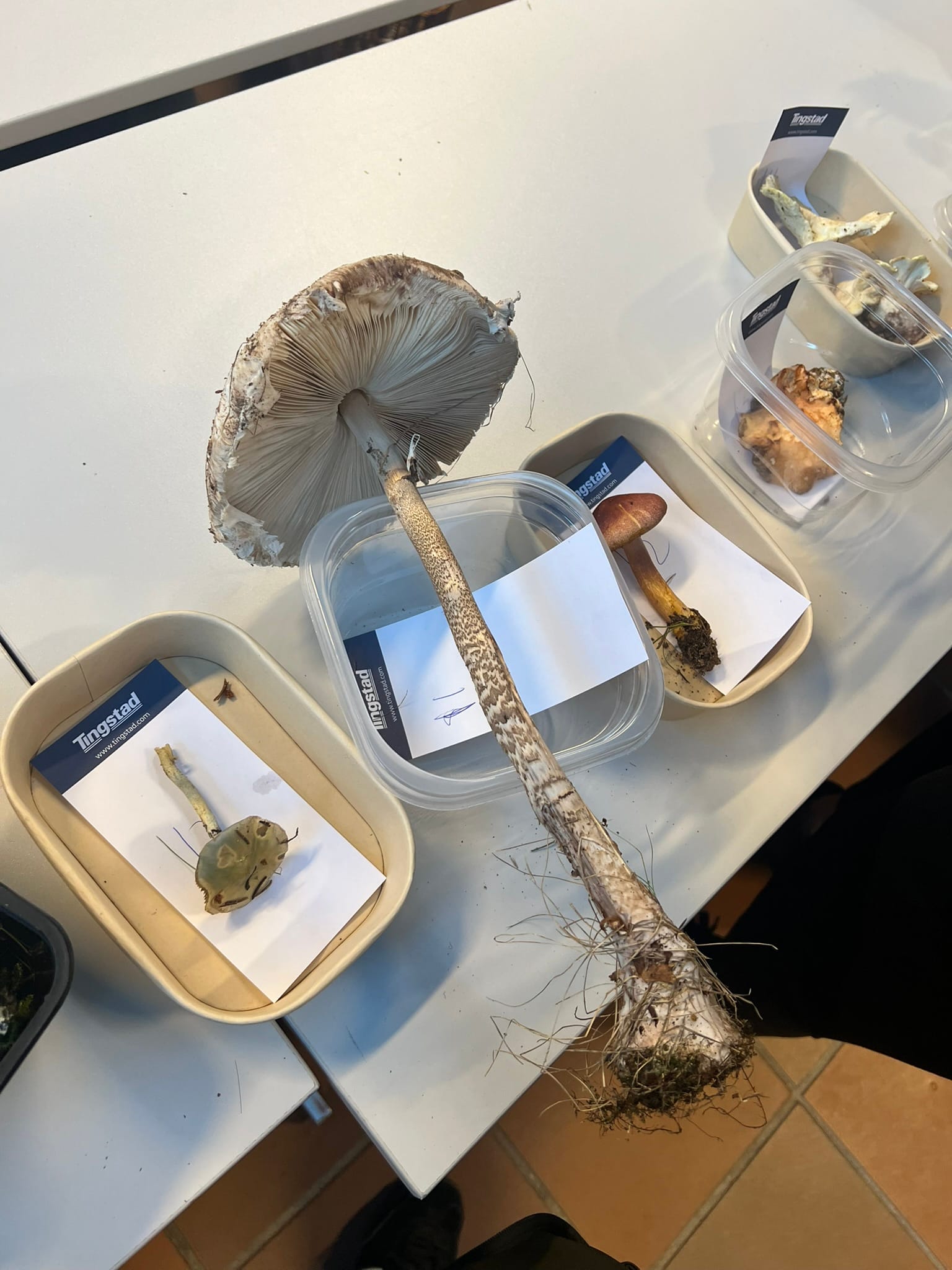

Just over a week before the exam, I attended an event in Oslo. Oslo’s local association hosted what is called an “examination table”. This is where a lot of different mushrooms are displayed and you can test your skills on them. I met a lot of candidates who were deeply into the identification.

I also met some that were taking this a bit too lightly. With the exam on the horizon, they barely knew the difference between a fly agaric and a chanterelle. For me that was an advantage as I had the chance practice my explanation of them, but I would’ve been surprised if they passed the exam the following week.

The following weekend saw the national association’s yearly mushroom meetup. This is a 3-day yearly event that gathers a lot of mushroom experts from across Norway, in addition to excited and hopeful candidates that are planning on taking the exam. The topic for this year was tricholoma, and received an identification key for the family developed by one of Norway’s leading mycologists, Gro Gulden.

On Friday and Saturday we had exhibitions. The weather was extremely wet, and it kept pouring down. It was not ideal for mushroom picking, and from the first day the majority of the mushrooms I picked were drowning into each other.

We also had the possibility to test our knowledge in the “examination rooms”. Here, mushrooms on the curriculum were curated and presented for everyone to test their skills. On the first day, I had a handful of errors out of 75 mushrooms. On the second day I had no errors out of 75, and I matched that on the third day with no errors out of 81 mushrooms. They changed the mushrooms between the sessions to keep it fresh.

This was a great way to learn, as I encountered several mushrooms I had never before seen in real life, such as the infamous tricholoma matsutake. This mushroom is highly sought in Japan and can in its prime be sold for thousands of dollars—depending on quality. In Norway, you will typically not get nowhere near that kind of prices for it.

The days leading up to the exam, I spent trying to get out and about and seeing as many mushrooms as possible. I attended any and all trips and events that the local association hosted and tried to go around on my own to see what I had.

On the day of the exam I went early in to Oslo. I spotted some mushrooms along the way and identified them as the sulfur tuft (Hypholoma fasciculare). It’s a bitter-tasting mushroom, and to put my senses in motion, I tasted a bit of it and—yup, it was bitter alright!

I arrived more than an hour earlier than I needed to in Oslo, and walked around the area. I heard rumors of there being yellow-staining agaricuses around the stock exchanged, so I walked there to find one. If you scratch its base or its hat, it will turn clear lemon yellow, which disappears and fades to a brownish gray after 15-20 minutes or so. It also has a distinct undefinable smell of medicine or hospital.

I headed over to the exam and was greated by a very nice, intriguing, and friendly woman who, upon my asking her role there, said she was there to “make us feel welcome and calm our nerves”. During my waiting, another candidate came, and we were talking there about how we had prepared for the exam and other things that happened. Then I got called in.

The exam room was a darker room with two people, the examiner and the evaluator, in addition to three desks or desk groups. One had 35 different mushrooms in various boxes. Another had the evaluator sitting behind. And finally the one where I was sitting to be presented the different mushrooms. There was a soft-light above to help see more clearly, but some of them such as sulfur tuft (Hypholoma fasciculare) versus conifer tuft (Hypholoma capnoides) were still difficult to make out in the light. In the back I saw a set of large fridges filled to the brim with various boxes and labeled with different mushroom name.

The evaluation system is point-based to avoid anyone lucking through the exam. The candidate will be presented 30 mushrooms. If they are correct, they will receive 0 points. If they are hesitating or seeming unsure, they’ll get 1 point. If they are providing the wrong status according to the norm list, they will receive 2 points. They will also receive 2 points if they are wrong about a mushroom where it doesn’t matter regarding its norm status, such as saying that the horse mushroom (Agaricus arvensis) is a meadow mushroom (Agaricus campestris). If you are completely wrong on a mushroom you will get 4 points.

If you get 12 points at any points during the examination, you fail. If you have between 8 and 11 points at the end, you will receive 5 more mushrooms that you need to identify, and the end result has to still be less than 12 points. If you were to have any of the four most poisonous mushrooms in Norway wrong, you will fail regardless of your total amount of points.

We got around to it, and I was speedrunning the mushrooms, identifying them and explaining their status according to the norm list, and what their potential poison timelines were. There was only one I got uncertain about, which I put aside. Otherwise everything was flowing. The one I put aside was a hebeloma with less smell than normal, and not its traditional “droplets” that can be seen by its gills. After examining it a bit I said that “this seems to be a hebeloma, which is classified as a poisonous mushroom in Norway”, which they said was correct. The evaluator said “well… I’ll give you 1 point for that, just because I can” and smiled.

They then looked at each other, before the examiner said “I don’t think we need to send you out to evaluate.” to which the evaluator agreed and said “No, I’ve already signed the diploma.”

In the coming weeks after, I attended and hosted 3 mushroom foraging trips with the local association, and we found several species I had yet to find for my examination. This year I managed to find all but 10 of the mushrooms on the curriculum list, and while some of them are relatively rare, others I’ve just not had the luck with. Now that the frost is hitting in the night, most mushrooms are not popping up anymore. So what’s next?

We’ve been fascinated with several parts of Pilze 123 and its search and filter functionality. While the Norwegian association for mycology and foraging has a good list with mushrooms, it’s not particularly user friendly to figure out if you’re finding something that doesn’t make sense. So could we develop a system and database that would provide the same type of functionality that Pilze 123 has, just better and more available for the Norwegian mushrooms? We’ll see what the winter brings until the season starts again!