A practical project framework for consistent delivery

Over the years, I’ve helped run and lead software engineering projects across different companies, domains, setups, and—naturally—people. While I’ve iterated on the framework over time, it’s become clear that there’s no single system that fits all organizations. Instead, I cherry-pick what I think has the greatest impact and add it on top of a solid yet generic foundation—workflow first, process second.

The framework is tool agnostic. I’ve recently had great success working with Linear, but it can be applied to anything. I have run it on Notion, GitHub Issues, and other project management tools without any problems. This flexibility makes it applicable across companies of various stages and teams of different sizes.

In this post, I want to share the framework I use to run projects. It’s a lightweight, pragmatic Kanban-based framework I’ve used across multiple teams. I’ll cover workflow, estimation, capacity, task quality, and backlog hygiene, and round off with the recurring rituals I use with my teams.

Terminology

For this writeup, I will use the terms Member for anyone who is going to do work on the project and Lead for whoever is leading the project. Projects outside software engineering will have different roles, but all roles should still fit within Lead or Member.

A Lead is a role typically filled by a combination of a Product Manager and a Tech Lead. There can be up to two Leads on a project, to cover the product and technology aspects, but this could also be a single person for smaller teams. The Lead leads sessions, follows up on tasks, and is ultimately accountable for the project’s deliveries and its ability to deliver.

A Member could be anyone, including a Lead. Typical roles I’ve seen here are Software Engineers, UX Designers, Analysts, Data Scientists, and so on. There are no fixed roles here, but the concept is that anyone working on the project is not guaranteed to be a technical person. This should influence how tasks are written.

Foundation

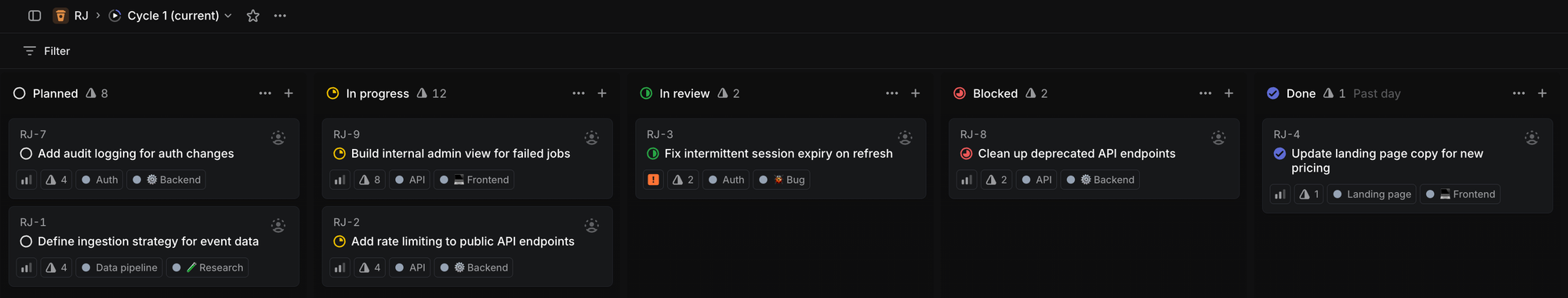

My framework builds on Kanban, with its states (or sometimes called “columns”) defined to be fit-for-purpose for the organization and—if applicable—the team. Well-defined states make it easy to get an overview and reason about where work is in the project’s cycle.

My must-have states are:

- Backlog: Tasks scheduled to be worked on in the future. The backlog should be somewhat prioritized.

- Planned: Tasks planned to be worked on and (mostly) completed this cycle.

- In progress: Tasks actively worked on.

- In review: Tasks awaiting or being reviewed.

- Blocked: Tasks that are externally blocked by something or someone outside of the team.

- Done: Completed tasks.

Moving tasks between the states should be cheap and low-friction. If possible, set up tools that will automatically put a task into the In review state when a pull request is opened, or set it to Done when the task has been merged.

Note that this assumes that QA or other, non-automated testing is done as part of the review, and that there’s no major deploy process. If you need to run work through more extensive testing or ensure quality in other ways, you could easily extend with a QA state. Without a dedicated QA-focused Member, I’ve found that a QA state often creates unnecessary bottlenecks.

If you need to create a build or a deployment, you could consider states such as Awaiting build or Awaiting deploy. I’m an advocate for rapid deployments, but I recognize that some software projects are more complex and will require such steps. If you’re in that situation, it might be possible to deploy parts of the solution in a more isolated manner to reduce blast radii, and thus increase deployment frequency. Just make sure that the extra states reflect real constraints, and not just wishful thinking.

Regardless of what specific states you choose, I recommend against having too many states, as that will quickly become a mess for everyone to stay on top of. A good rule of thumb is that the cycle’s status board should fit within one laptop screen.

Estimation challenges

If you ask anyone managing a project what they find the most difficult, chances are they will say estimation. I’ve heard from non-technical and technical people how challenging it is to figure out how much work a task involves and how much they can take in during a cycle.

Over the years, I’ve heard various estimation techniques, mostly with tongue in cheek remarks, such as “just multiply the estimate by pi” or my favorite joking aside: the developer’s estimate. Take the lowest estimate around the table, add one and increase the time unit by one. 1 hour? More like 2 days! 1 day? See you in 2 weeks!

Estimation is hard to get right—and I believe no one ever gets it perfect—but getting it severely wrong will impact your team’s health through less meaningful planning, lower delivery throughput, and worse delivery predictability.

I’ve tried arbitrary points, T-shirt sizes, no estimation, and eventually time-bounded estimates. It’s the latter that I’ve seen the most success with, but in order to explain why, I want to first touch upon what went wrong with the others.

For the arbitrary points, the problems mostly arose through not knowing the unit of measure: With a budget of 53 points, is this a 3-point task or a 7-point task? We ended up vastly underestimating the tasks, and overloading the team with tasks it had no chance of ever delivering on.

T-shirt sizes almost worked for my projects, but two things kept messing it up in practice: people came in with different baggage of what the sizes meant, and it was hard to figure out how to translate a given amount of T-shirt sizes into a cycle’s budget. (Come to think of it, should we go all out and name such a budget “the laundry”?)

No estimation is often preferred over bad estimation, but from my experience, this also tends to create large tasks that are all-encompassing and easily susceptible to scope creep due to a lack of constraints.

Bounding work with time

After some trial and error, I landed on time-bound estimates. This is probably the most boring approach, but in my experience also the easiest to get right. For this to work, we need to lay out a few ground rules for tasks:

- No task can be less than 4 hours of work. If you think about even the simplest coding task, it will need to go through a code review, CI/CD pipeline, potential testing, a refill of the coffee mug, and writing a good and descriptive commit message. Even if the task were to take only 1 hour of coding time, taken together, it quickly adds up.

- No task can be more than 5 days of work. This prevents evergreen tasks that are stuck as In progress for weeks on end without clear signals of progress. The only exceptions to these are tasks that are composite, exploratory, and research-focused, such as UX or tweaking infrastructure configuration.

With these two rules in place, we can start structuring this. I’ve landed on using a points scale, where each point represents half a day. This could also be explicitly set as the time values themselves, but the points make it easier to see how much we can do in this cycle.

As a concrete example, this is how I’ve set it up in Linear, but the approach applies elsewhere too. In Linear, I’ve chosen “Exponential” under Estimates settings without extended scales and without allowing zero estimates. That leaves us with this scale:

- 1 point: 4 hours

- 2 points: 1 day

- 4 points: 2 days

- 8 points: 4 days

- 16 points: More than a week—needs to be broken down!

Cycle capacity

I’ve yet to see anyone spend 100% of a week solving tasks. There are team meetings, bug reports, pair programming, code reviews, and a lot of other in-between tasks across the organization that can’t and shouldn’t be tracked within a project management framework.

Thus, we assume that the max capacity for a Member is 80%. If the Member has other roles, or is fractionally available to the team, their capacity should be further adjusted. For example, if we expect that the Tech Lead is going to spend 25% of their week on management and other overhead work that isn’t tracked in the project, their availability will be 80% of their 75% max capacity; 60%. Note that for very reactive and operations-focused teams, such as an infrastructure team, this max capacity for task solving might be lower than 80%.

Combined with the estimation foundation we laid out above, we can now calculate the max cycle capacity of the team. First, we figure out the total available days for the team:

\[D = \text{sum of available days across the team}\]

Then we scale this using a as the team’s availability (e.g., 0.8 for 80%):

\[C = a \cdot D\]

We can finally convert to points by multiplying by 2 (as 1 point = 0.5 days):

\[P = 2 \cdot C\]

Example: Our cycle length is 1 week. We have 3 Members who are available all week, and two who are available only three days. The team’s availability is set to 80%. The cycle’s max points would then be:

\[D = (5 + 5 + 5 + 3 + 3) = 21\\C = 0.8 \cdot 21 = 16.8\\P = 2 \cdot C = 33.6\]

This shows that the cycle’s max capacity would be around 33 points.

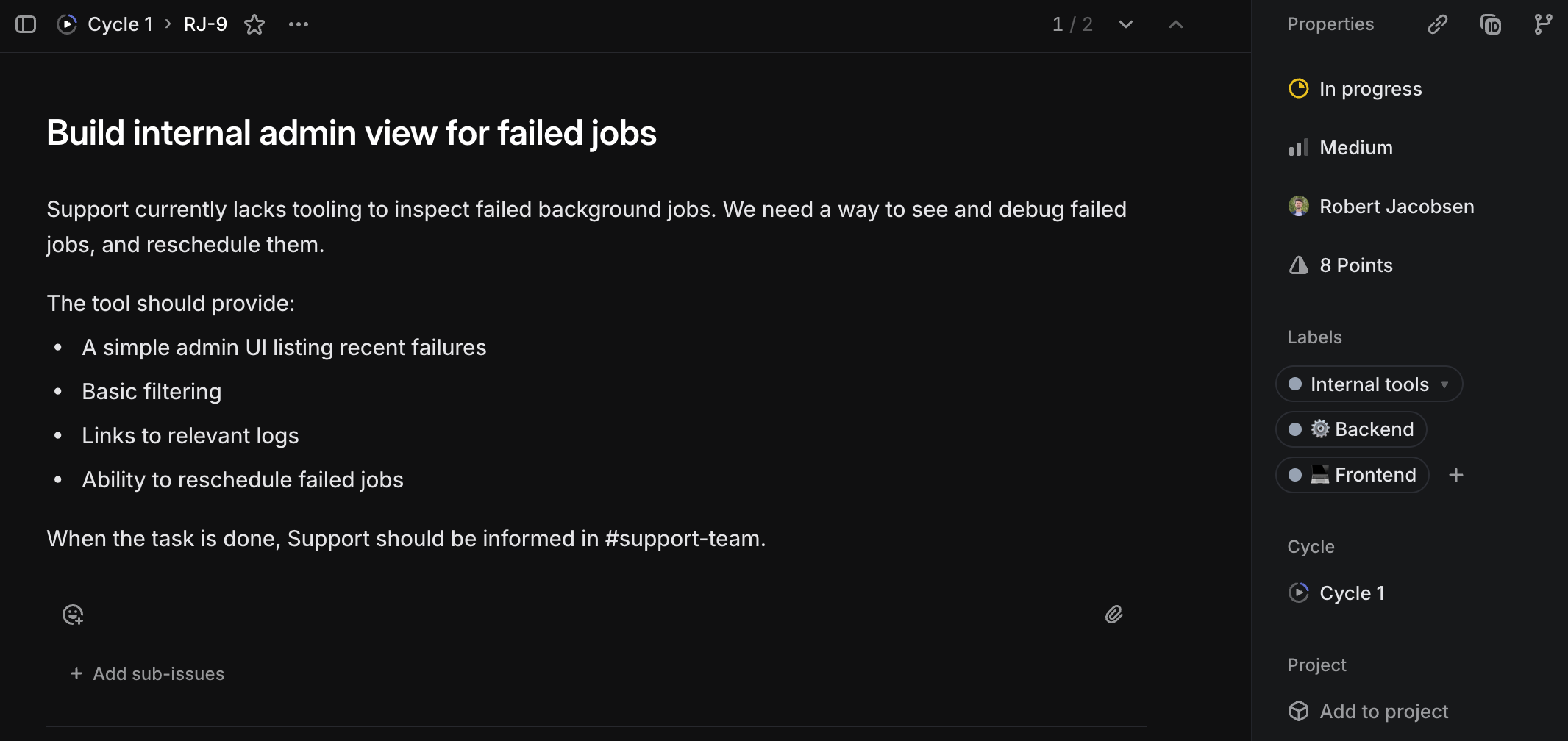

A well-written task makes it easier for everyone

At a minimum, a task needs a title, description, priority, and estimate. Everything else is optional and should only be added when there’s a specific need. That said, there are a few things that I think a good task should have.

First, I want to stress how important it is to have a good title and a description that explains why something needs to be done. The title will often be what people see and remember the task by in every planning session, backlog refinement workshop, or standup.

The description will help both the Members who will work on the task and the Leads who will prioritize the task and explain its importance to stakeholders. It should address why we’re doing something and what we hope to achieve, but not go into details about any hows (unless the hows add constraints, such as saying this has to be done in a certain way because of external constraints).

One custom property I often revert to is a task type. This is a multi-select property that describes the nature of the work or the area it touches. It could be one or more of the following:

- Research: A task whose sole purpose is to figure out how to do something. The output is often a specification or proposal to be shared with the team, alongside follow-up tasks for implementation or further research. The estimate represents how much time may be spent, not how long the work is expected to take.

- Backend, Frontend, Infrastructure, Design, Data, AI, Developer Experience, and other fit-for-purpose areas to indicate which type of work this task encompasses. This will help categorize and classify the task so it’s clear who should work on it.

- Bug: Something that has been reported as a bug.

- Documentation: A task that consists of writing documentation for the future, making documentation a first-class citizen among other tasks.

- Technical debt: A task that addresses earlier technical trade-offs and shortcoming introduced by taking shortcuts to ship a release.

In addition to the above, I also try to add a single-select component property, which indicates the primary component it touches. I’ve had varied success with using this, but it’s given me nice insights into which components are receiving the most (planned) work. Making this component single-select also helps keep tasks scoped.

Employing fit-for-purpose properties allows you to easily extract reports to see how many bugs you squash per cycle, or how many infrastructure tasks are in the pipeline. This is one of the areas where I customize the project the most for the needs and missions of the teams, but the core concept should be aligned across multiple teams in the same organization to avoid chaos and misalignment.

Keeping work moving

One of the most common handbrakes I’ve experienced is when work is done but then waits multiple days for a review. Everyone’s busy with their own tasks, and there’s no good mechanism for reviewing consistently. This is particularly bad for written code, since the task’s output will not be in use before someone’s approved and merged the pull request.

Ownership of the task stays with the implementing Member throughout the task’s lifecycle; whoever is working on the task is responsible for following up on it until it’s deployed and marked as Done. This also means that if the task’s deployment requires special treatment, the implementer is responsible for this too.

If a task gets stuck waiting in In review, the implementer should actively seek out a review—whether that means nudging a teammate, sitting down with someone for a joint review, or booking dedicated time to go through it with someone (I’ve found joint reviews to be a great way to share knowledge). Keeping work moving is a shared responsibility, but it needs a clear owner.

The same applies to work in progress. I encourage limiting how many tasks a Member has In progress at the same time. Ideally, this is one. If work has stopped, the task should be moved back to Planned, marked as Blocked, or closed as canceled if it’s no longer relevant. Stale In progress work hides problems and slows everyone down.

Reviews should be treated as real work. Teams should have explicit routines for handling them—whether that’s at the start or end of the day, or around lunch. The exact timing matters less than the habit. What matters is that reviews happen continuously, not in batches every fortnight.

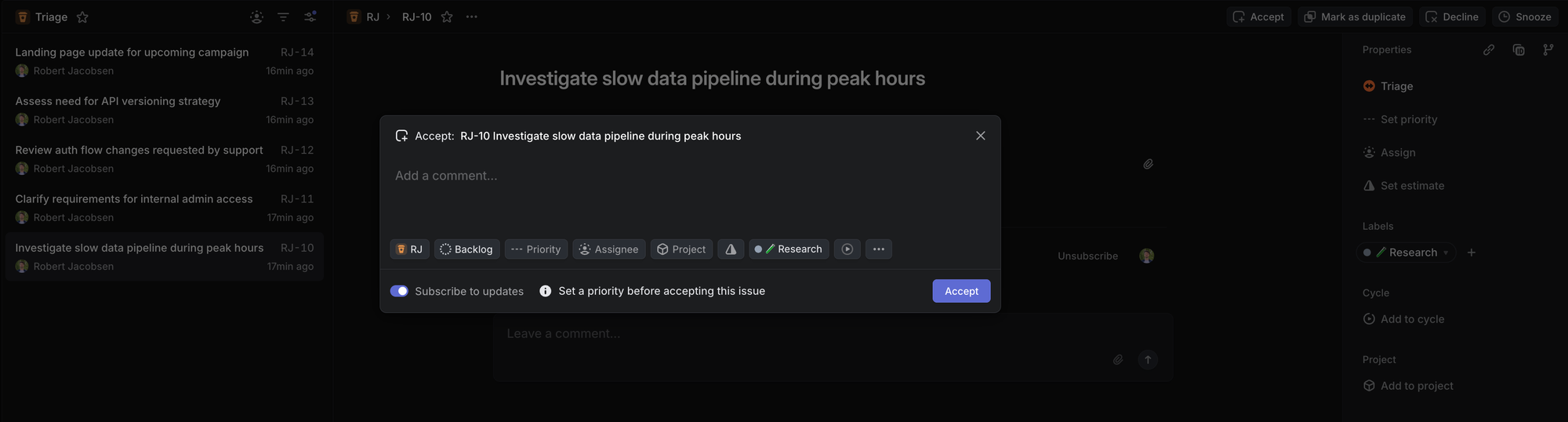

Triage

Depending on the maturity of the project and the number of people working on it, running a triage session shouldn’t necessarily be the first priority. I use triage to ensure two things:

- Everyone on the team should have a basic idea of what this task is about whenever it’s picked up in the future.

- The task should have its basic properties set, such as priority, estimate, and required tags. It should also have a descriptive title, a helpful description, and links to any related tasks.

When possible, I don’t approve tasks out of triage unless they meet these criteria. That said, not every single task needs to go through triage. If the task needs to be dealt with this cycle—think a critical follow-up from elsewhere in the organization—then it doesn’t make sense to involve anyone else beyond the executing Member and the Leads.

Once accepted from triage, the task will be placed into a cycle as Planned or into the Backlog.

Culling the backlog

A common truth is that tasks are often put in the backlog to die. There are some tasks that are always deprioritized and never get into a cycle. I typically end up addressing these through a backlog refinement workshop.

The backlog refinement workshop is a place where the team jointly navigates through the backlog—preferably from oldest to newest—and answers these questions:

- Do we understand what this task is about?

- Is this task still relevant?

If the answer to either of these questions is “no”, we need to do something. The simplest case is when the task is deemed irrelevant—then we close it. If the task is considered relevant, but no one on the team understands what it’s about, someone needs to revisit the task’s deliverables. This can mean assigning someone to fill out a task for the next triaging session, or—in case this is a larger piece of work—creating a new research task for it.

In the event that the answer to both of these questions is “yes”, the next question is when. We want to figure out the priority and how pressing this is compared to other things in the backlog. Use the priority property for this.

Addressing technical debt

When we push hard to release a feature, we often need to take shortcuts. These shortcuts come with various trade-offs and shortcomings that need to be addressed at some point. This is what we call technical debt.

Often the technical debt is pushed under the rug until it’s bulging on the floor and bursting at its seams. Instead, I advocate for a more continuous repayment of technical debt.

With each cycle, we should pay some technical debt down. My rule of thumb is that for each week in a cycle, at least one developer day worth of tasks addressing technical debt should be planned into the cycle. Depending on the size of the team, this could be more.

Retrospectives

One of my favorite things is taking a step back and reflecting on what’s worked well and what hasn’t so that we can iterate and improve as a team. I typically break this up into two types of retrospectives: team and delivery retrospectives.

For the team retrospective, the scope is to figure out what has worked well—and what hasn’t—for the team. This is a recurring retrospective, and I aim for one every 6-12 weeks, depending on the team size. The output should improve our way of working within the team, and ideally give us 2-3 takeaways for improvement.

A delivery retrospective is held on-demand with everyone involved once a feature or a larger piece of work has been delivered, something that typically takes weeks of cross-functional collaboration. While the same group of people will usually not work together again, the output of the retrospective should be openly shared as lessons learned with others who may work in a similar way.

When I facilitate retrospectives, I aim to make them as easy to attend as possible. I use a combination of colored post-its for start (yellow), stop (red), and continue (green), where everyone is given a stack of each up front to write down their answers to:

- What was missing that we should start doing?

- What did not work that we should stop doing?

- What went well that we should continue doing?

In the retrospective, we go through all the stickers for each of these points in order. First we begin with start, and let everyone go in order to explain what their stickers are and put them up on a wall. We cluster them naturally as part of the process. Discussion isn’t allowed during this phase, but clarifying questions are (“Where did you experience X?” is OK, while “How would you deal with Y?” is not). When everyone’s gone through their start stickers, we go on to stop.

Stop has one special rule: You can’t tell something to stop without giving an idea of how to address it. I once had a colleague who was very much the “glass is half-empty” kind of person, and when it rained it poured. After a session where we got 10 post-its describing how everything was bad and working against them, this rule came to be. Surprisingly, it worked—for the better! I now receive more constructive input, including from people who tend to be more positive.

You may also notice that start and stop complement each other. This is by design, as it helps surface issues that affect people differently. I often find stop stickers that have a counterpart start sticker first. This is where color-coding helps when we group them.

Finally, continue is mostly our good pat on the back, but it’s still important to recognize what we’re doing well that shouldn’t get lost among all the improvements we want to make. A good iteration is when we can bring something new to the table without losing what already made us good.

Then everyone gets 3 votes to select the clusters they think should be improved. This part can be skipped if this is a delivery retrospective, or if there’s not enough variety of clusters.

After the session is done, the facilitator takes pictures and writes down a summary of the retrospective. They then work with the Leads to come up with concrete suggestions on how to address these, where the Leads can present in a team meeting.

Recurring rituals

Companies have their own meeting policies, teams have their own rhythms, and the flow of deliveries makes every cycle different. This makes it particularly important to have common points for planning, reflecting, and checking in.

I use different rituals depending on the needs, maturity, and size of the teams I work with. When I introduce a ritual, I make sure that it’s fit for the team while also giving me the insights I’m looking for.

- Check-in: This is the most frequent meeting, and something that could be done async (though my experience is that insight often gets lost as people rush to write down their status and don’t read what others share). A 10-minute check-in is a good daily routine, where anyone not in the office dials in.

- Cycle planning: I’ve had success with this either at the start of a cycle, or at the end of the previous one. My go-to is the latter. The advantage is that everyone will know what’s in the cycle when they check in with their morning coffee on Monday. I’ve seldom encountered any priorities changing between Friday and Monday. I schedule this for 50 minutes.

- Backlog refinement: As outlined above in Culling the backlog. I typically have this at most every two cycles, and schedule it for 50 minutes.

- Retrospective: As outlined in Retrospectives. I schedule a retrospective for 50 minutes.

For all rituals, I avoid mixing them into the same meeting. They should have their own agenda and focus. The only exception is cycle planning, where we can spend a few minutes for non-cycle discussions, such as follow-ups from retrospectives.

When I navigate the project’s overview, I always start as far to the right (towards Done) as possible and go column by column to the left. I generally don’t touch Backlog unless we’re doing backlog refinement or cycle planning. I also avoid Planned in check-ins unless we’re at risk of running out of tasks (which, honestly, rarely happens), or if we need to push something to a different cycle due to taking new (critical) tasks in.

Note that these are all on a team level, and that there are probably going to be overlapping department-level meetings for sharing knowledge, giving status updates, and similar purposes.

Consistency over perfection

All of the aspects I’ve outlined above have helped my teams deliver more consistently, but as I’ve said—what works for one organization is not guaranteed to work for the next. Your challenges will be different from mine, but hopefully this writeup has given you some ideas worth trying in your own context.

Feel free to be inspired, copy, iterate upon, and improve any of the ideas. If you have any success—or maybe even more interestingly, if you don’t—I’d love to hear about it.